Fencing, Old and New. *

As Typified by Angelo and Prévost.

Journal of Western Martial Art

April 2003

by H. A. Colmore Dunn

Originally published in Outing magazine, October, 1894, No. 25, p. 29-34.

Pour être bon tireur, il ne suffit pas de se présenter de bonne grace, de tirer avec vivacité et justesse. Le grand point est de savoir se défendre et parer les coups que l’adversaire tire."

In a serious assault between two good fencers, parry and riposte are still the keystone, and on the dueling field this is urged with even more insistence by the professors of the most recent development of the art of fencing, the much traduced and little understood jeu de terrain or jeu de l’épée, as it is indifferently called, to distinguish it from the jeu de fleuret or jeu de salle. A very cursory glance at the remarkable published in 1887, written by the Parisian professor M. Jacob, with the collaboration of M. Emile André would suffice to disabuse the mind of the most prejudiced person who is inclined to sneer at the distance dividing two inexperienced duelists which lends such enchantment to their view of the adverse point The jeu de terrain is not, as its drawing room critics assert, "like the operations of two long-necked birds hopping backwards and forwards with extended bills." As stated inaccurately by some who think they would like to fight on the field with all the freedom, not to say license, of the fencing-room, the jeu de terrain is described as pecking at the extremities, then breaking ground and pecking as you break, or, in other words, as being an easy way of combining the fame of the fighter with the security of him who runs away. On the contrary, the dueling game must be only too deadly as played by a competent exponent. Launching the point at head or hand or arm is only the beginning, the elementary side, and in the hands of an expert, the same maneuvers serve as feints or false attacks, by way of skirmishing in order to force the opponent to give his blade or to induce him to make some move which may furnish an opportunity to shatter his defense and lead up to a riposte on the breast. In the words of the Introduction, "le jeu le plus sûr pour tirer au corps est le jeu de parades et de ripostes, avec les contreripostes. Nous arrivons là au véritable fond de nos leçons d’épée." In short, the same principles lie at the bottom both of the jeu de fleuret and the jeu de terrain, and it is not so much that the coups differ so much in kind, as that the application of them is subjected of necessity to far more rigorous limitations on the field.

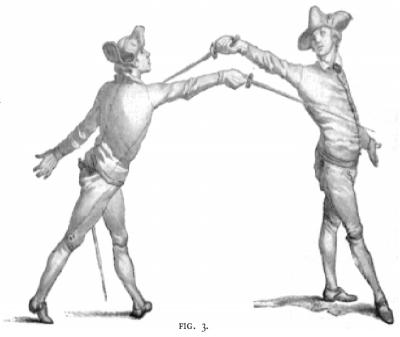

The point of severance between the two styles is to be found in the simple and striking fact that on the dueling ground all hits score, and it would be very cold comfort to endeavor to stanch a wound by the possibly truthful stricture that the stroke which dealt it might have caused dissatisfaction to the captious critic of the school. Before tilting incontinently at the breast of an opponent armed wit a sharp weapon, it is wise to take the preliminary course of getting his point out of the way.  The neglect of this simple precaution very nearly settled a difficult problem in contemporary French politics when the late General Boulanger rashly tried conclusions between his throat and the business end of his opponent’s sword. On one point, to which M. Jacob calls fig. 3. particular attention, there is a curious difference of opinion between him and Angelo.

The neglect of this simple precaution very nearly settled a difficult problem in contemporary French politics when the late General Boulanger rashly tried conclusions between his throat and the business end of his opponent’s sword. On one point, to which M. Jacob calls fig. 3. particular attention, there is a curious difference of opinion between him and Angelo.

Journal of Western Martial Art

April 2003